If you had told me six months ago that Andy Murray would hold the year-end number one ranking, I would have called an insane asylum.

How? How could he pull it off? Djokovic had beaten him at every turn—the Australian Open, Miami, and even in a momentous Roland Garros final, where Djokovic became the first man since Rod Laver in 1969 to hold all four grand slam titles simultaneously.

Djokovic was the better player. Murray’s second serve was too slow, his forehand too flat, his temperament too volatile. Anything Murray could do, Djokovic could do better. Just a few months ago, I had written about how Djokovic could be the greatest of all time. Djokovic was just too good.

Getting to the number one ranking was a massive ask. Djokovic’s point advantage was tremendous. But Djokovic blinked after his French Open triumph, the victory sating his appetite for titles.

Murray, however, grew more ravenous.

The man from Dunblane was not content to sit and wait as second fiddle. He worked on his game—his forehand got harder and his second serve heavier. Instead of being distracted by the birth of his daughter, fatherhood calmed Murray. Perhaps most importantly, he hired Ivan Lendl, the iron Czech who had coached him to his previous two Grand Slam titles.

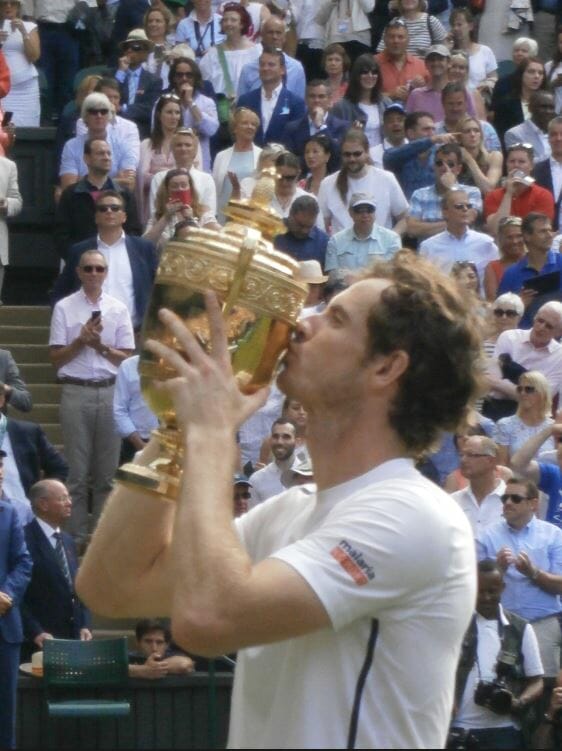

Murray won Wimbledon. Then the Olympics. Then Shanghai and Paris. Somehow, Murray clawed his way up, with Djokovic in the distance but growing ever closer.

The poetic nature of sport—and its allegory to war—comes out most in a showdown between two great rivals. Just this kind of occasion happened on Sunday, November 20, when Djokovic and Murray were set to square off in the final of the ATP World Tour Finals—the last match of the last tournament of the 2016 season. The winner would take the number one ranking, and a page in the history books.

Would number one triumph over number two? Would Djokovic defend his title for a record fifth time, or would Murray become the first British number one ever?

The odds didn’t seem stacked in Murray’s favor. He played a grueling, scrappy three-hour match with Milos Raonic-not even twenty four hours before his matchup with Djokovic, while Djokovic had dismantled Kei Nishikori the day before. Murray had won only 10 of their previous 24 matchups.

But somehow, Murray did it. He released a barrage of backhands that buffeted Djokovic far behind the baseline. Forehands dipped in, serves zipped by Djokovic’s flailing arms. The unbreakable Djokovic seemed unstable, like he was fighting for every point. But Murray was now the epitome of untroubled cool, dutifully rocketing passing shoots past Djokovic’s racket as he lunged for the ball. When the match was over, Murray dropped his racket to the court, staring at his camp in disbelief. Djokovic had been taken apart, clinically: 6-3, 6-4.

Murray is now number one. With every shot he hit on Sunday, Murray proved how much he’s grown. Murray is a different man—a better man—now than he was when he entered the circuit. The erratic nature of youth has been replaced with the refinement of maturity.

Murray is king now, and he’s earned every step of the way.