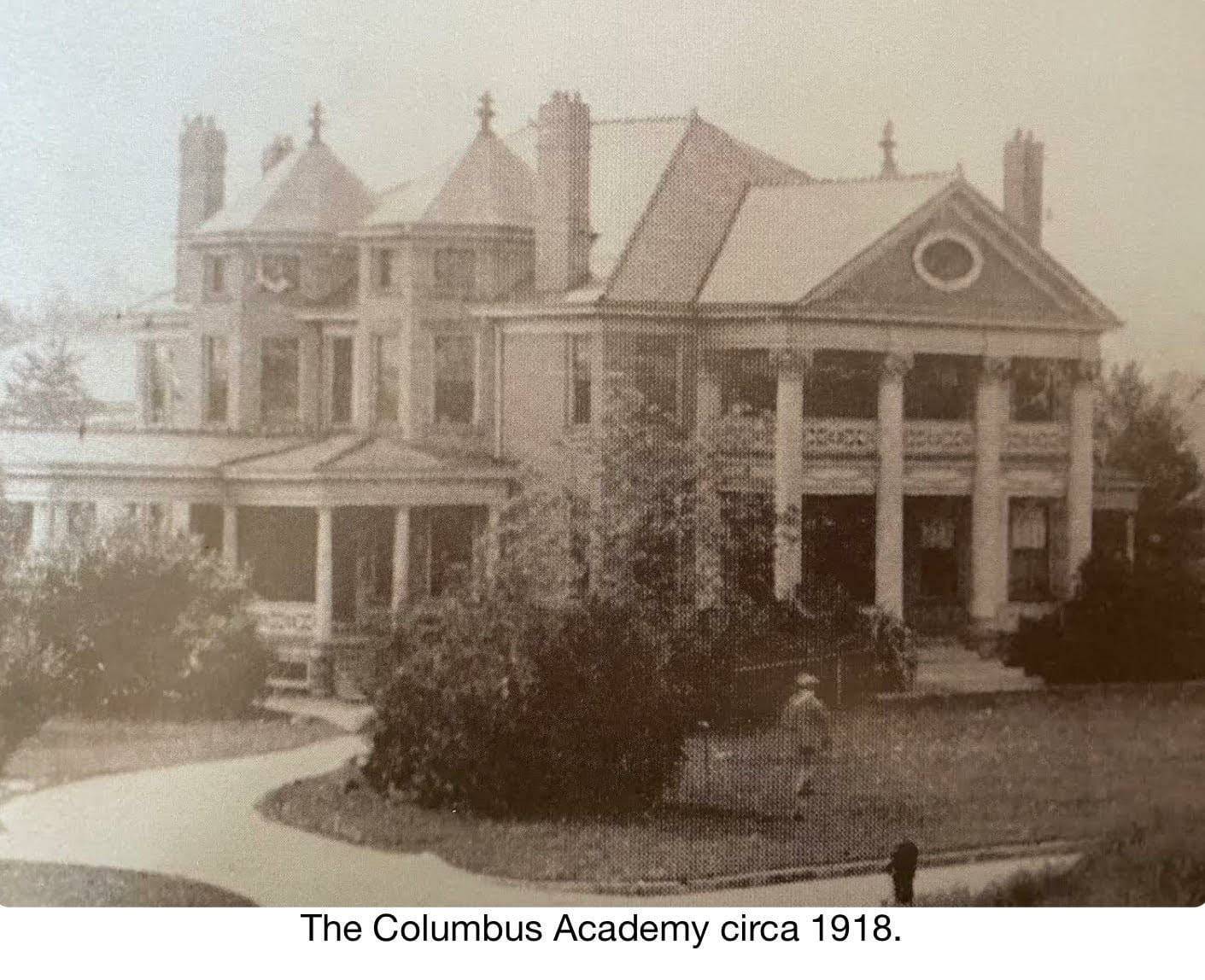

In 1918, it wasn’t the Spanish Flu that was weighing on the minds of Academy boys. The boys were much more distracted by the prospects of the Great War.

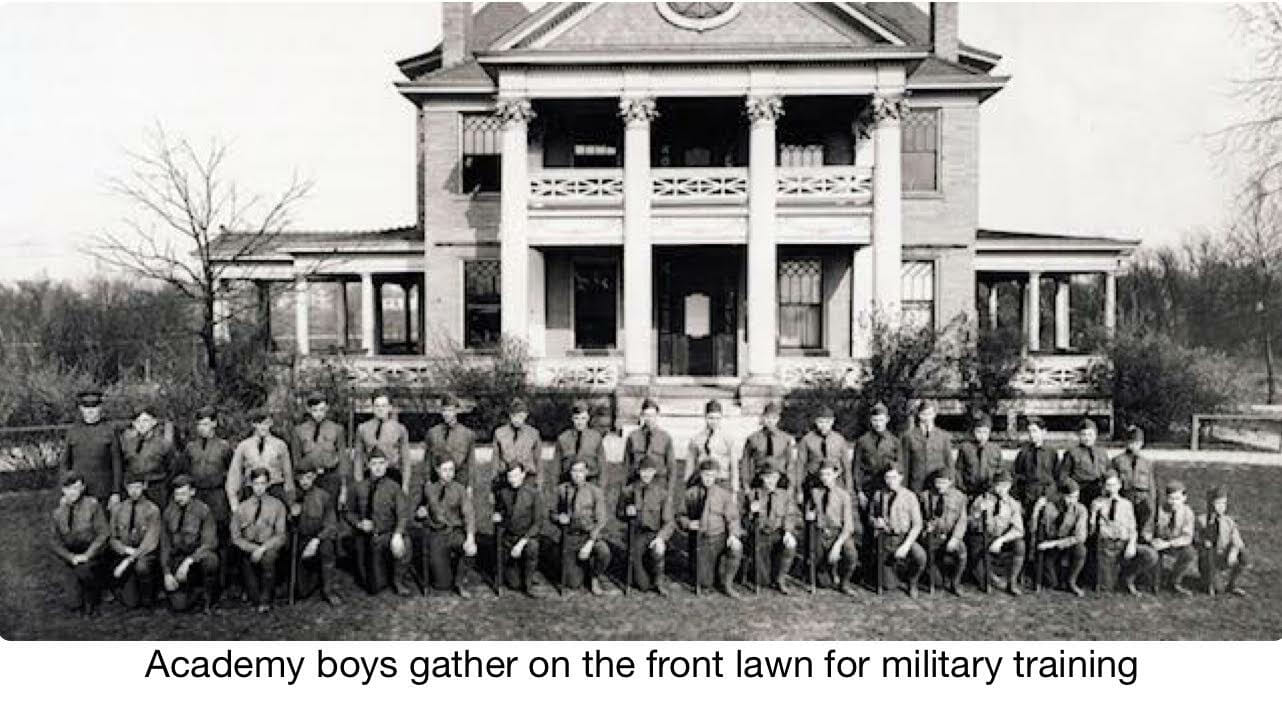

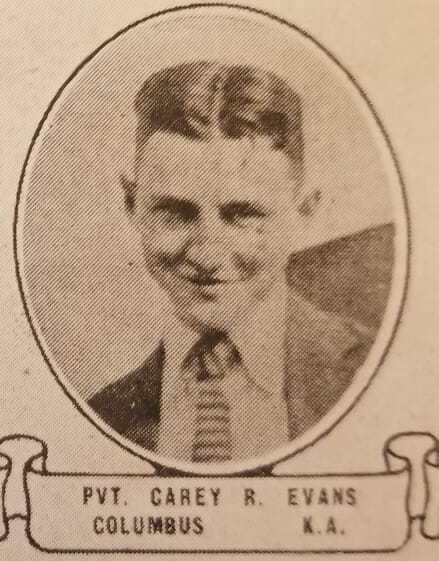

While their classmate, Carey Evans’14, and beloved teacher, Master Albert Field, were off fighting in Europe, Academy boys continued to train on the front lawn with uniforms and “dummy” rifles, a military tradition Field, himself, started.

In the 1919 edition of the Caravel, Headmaster Frank P. R. Van Syckel reflects, “The fact that only a very few of the Academy students . . . seemed at all likely summoned to military duty made no difference.”

“The unwillingness of the fellows to remain longer inactive and wholly out of touch with the big enterprise in which America was engaged was too strong to be denied. The uniforms were ordered, the ‘volunteers’ came forward, the march began, training was initiated, and the small campus in front of the school building, where heretofore nothing more war-like than a game of tag or first-team signal practice at recess had occurred, now became a Campus Martius, and Academy Army reeled and turned, eluded telegraph poles, and charged the shrubbery.”

On April 5, 1918, they received the news that Evans, an ambulance driver in France, had died. Evans was in the first graduating class at Academy and was the first alum to die in conflict.

And while the war against the Kaiser continued, there was another enemy lurking in the shadows that would pose a threat to those on the home front.

“No sooner were we in full swing–with such difficult questions settled as to who was to take Latin; who Chemistry; who Physiology; who were to be the ends and who the half backs in the football team; how many swims per week would be allowed; who should be expected to enter the school by the front door, etc.; then we woke up one morning to discover that all questions were tabled, for school was closed!” writes Headmaster Van Syckel.

He continues, “The influenza was in our city, perhaps within the fellow who sat next to us in Math, or at table, — and the first and foremost duty for everyone was to avoid human beings, live in the sunshine, commune with nature, speak with the birds and squirrels, but not with a neighbor — in short, keep oneself so strong and well that the little Spanish ‘Flu’ would be compelled to pass each and everyone by, as impervious to attack.”

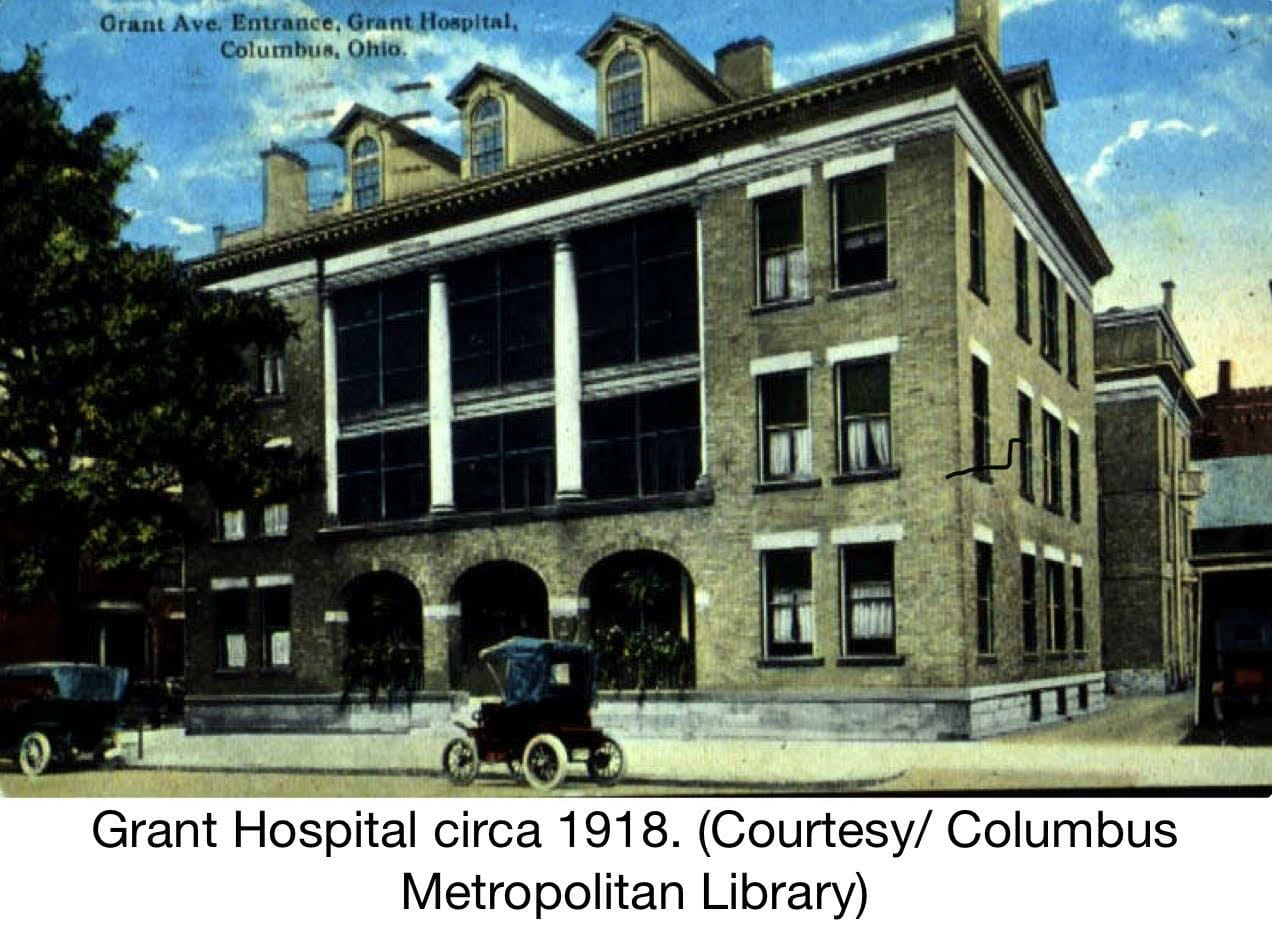

Nearly two weeks before schools in Columbus were closed, Dr. Louis Kahn, Columbus Health Officer, had assured the public, “There is no need to worry so far as Columbus is concerned. The epidemic appears to be at its peak and we can look for a lessening of the number of cases within a few days.”

On October 8, the headline of the Columbus Evening Dispatch read: “Danger of Influenza Epidemic is Remote.”

Three days later, Dr. Kahn decided to close “indoor amusements” such as theaters.

Surprisingly, the churches in Columbus were closed while the saloons remained open. Some speculate that it was because laborers relied on the saloons for their daily meals.

Not surprisingly, Ohio State football played two more games before their facilities were shut down (“O-H”).

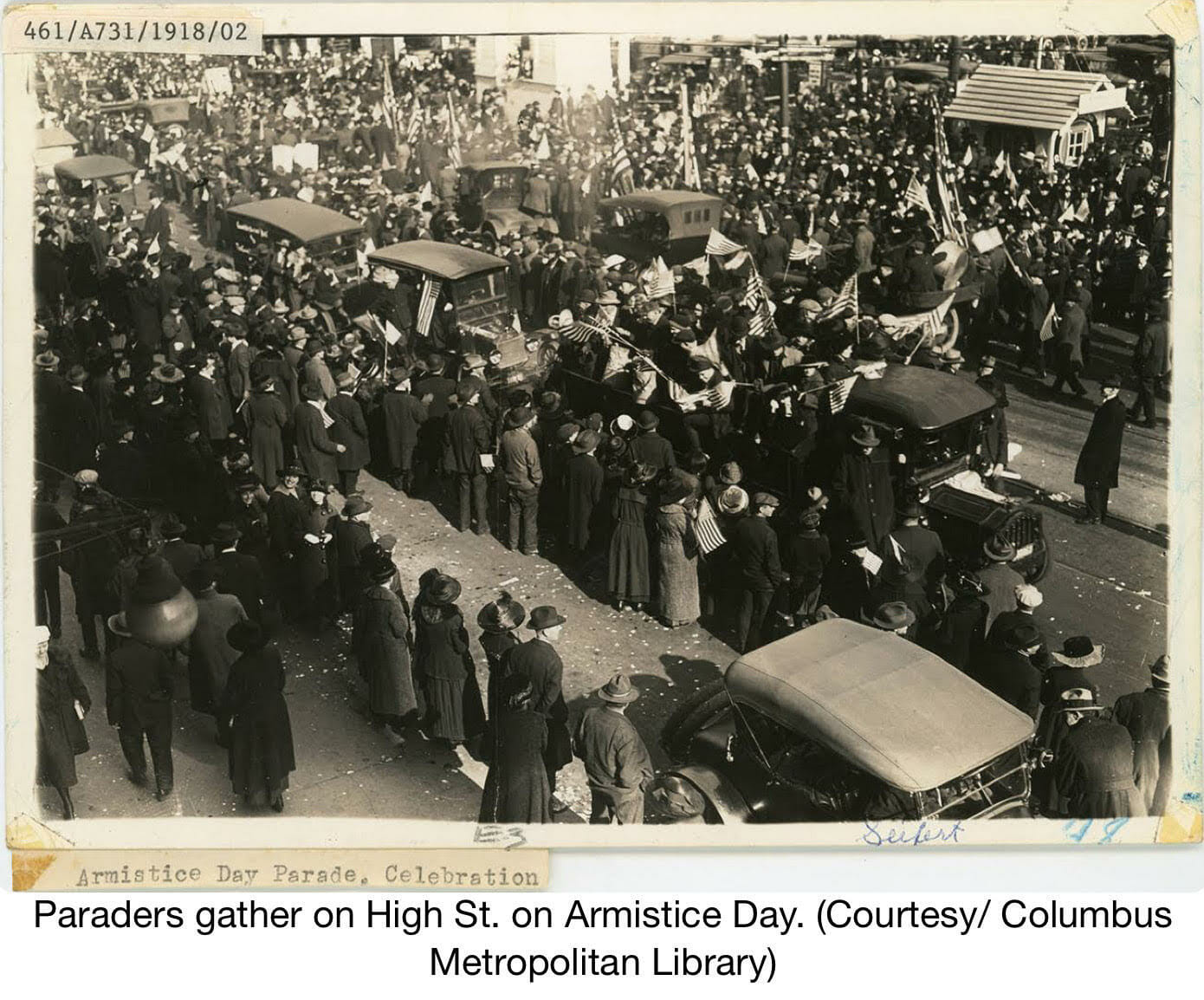

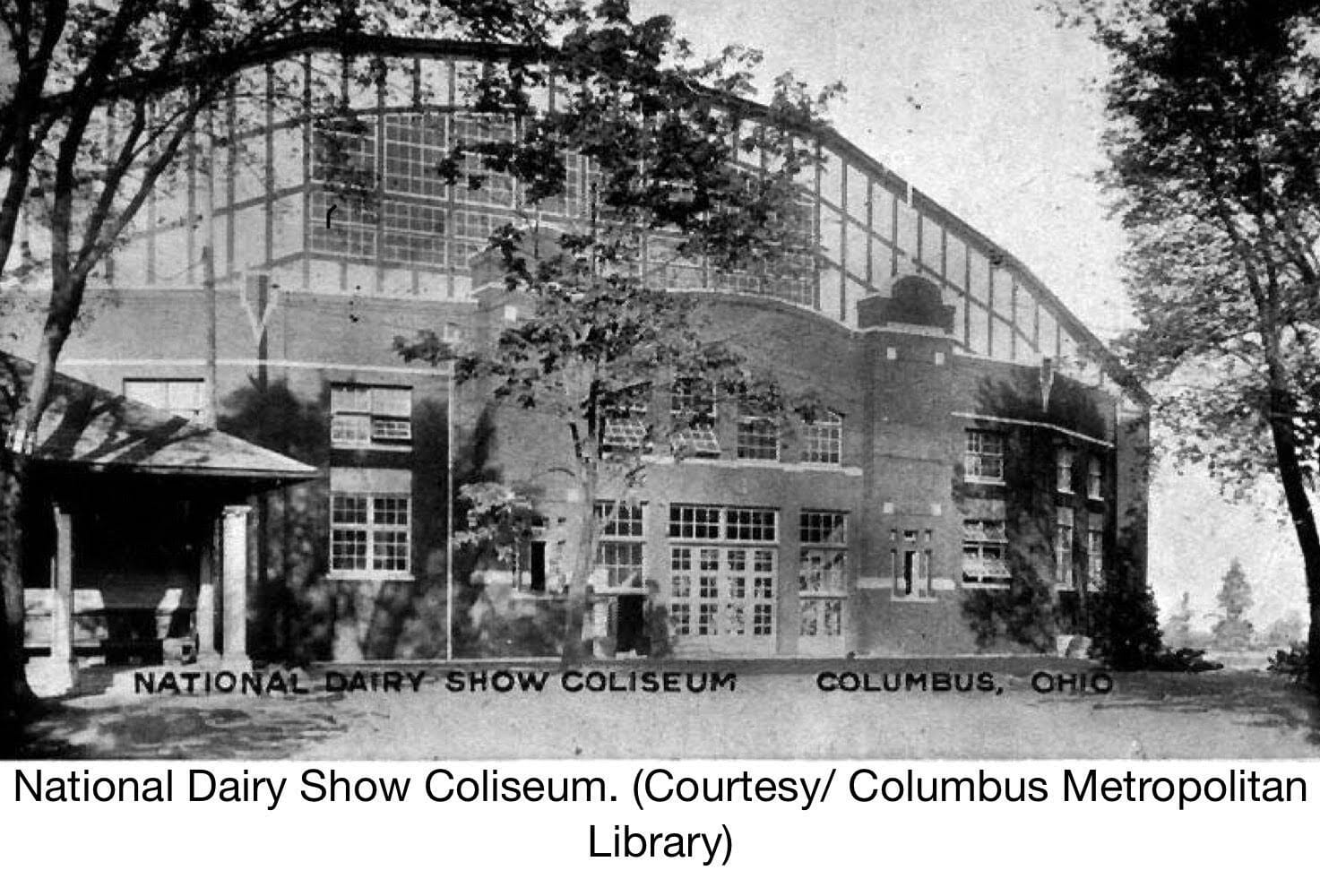

Under pressure from the Ohio Chamber of Commerce, Kahn did not cancel a concert at Memorial Hall and the National Dairy Show at the fairgrounds. Regarding the decision, the Evening Dispatch described, “It was argued that only the best class of people will attend the concert.”

Yet with flu cases dramatically rising, all schools in the state of Ohio were closed on October 14th. The Dairy Show, however, still scheduled for the 16th, was not. Visitors from Ohio and beyond crowded in the fairgrounds to visit booths that showcased the dairy industry, despite the fact that almost one thousand citizens of Columbus had caught the Spanish Influenza.

Academy, like the city of Columbus, did not entirely grasp the scientific reasoning for “social distancing” and its consequences. In fact, teachers conducted “home visits” for student learning.

To great relief, fortune favored the school. Van Syckel writes,

“. . . very few cases amongst our students were reported. Meanwhile, the weeks were passing, wonderful football days, as well as excellent football prospects, were being wasted.”

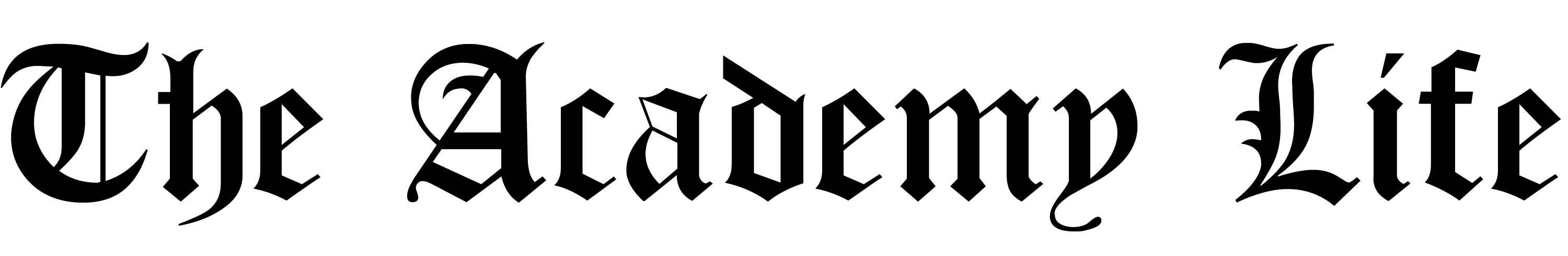

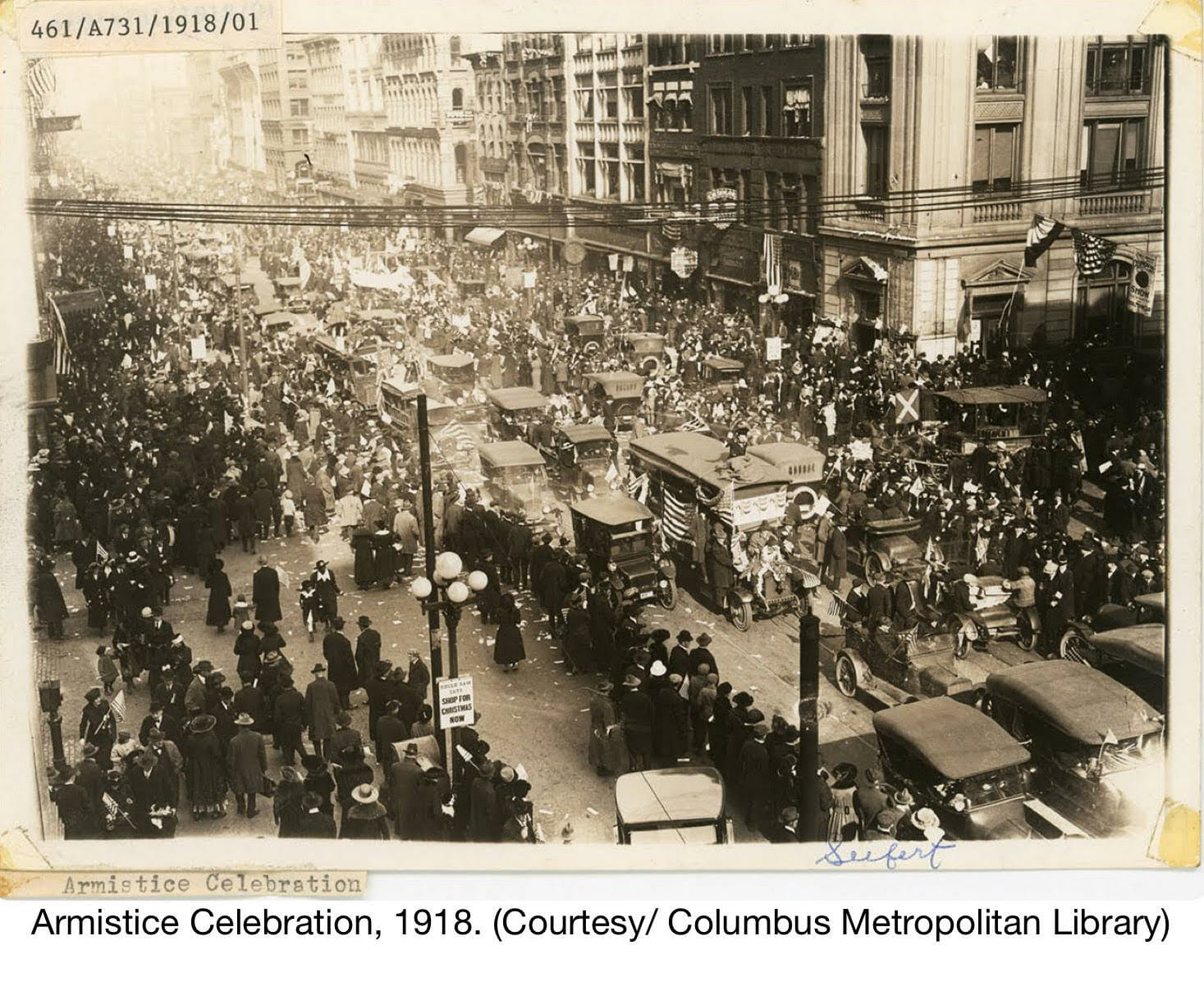

When the war ended on November 11th, 200,000 people paraded through High Street to celebrate victory. On this day, the crowds seemingly forgot the dangers of the virus. Paraders linked arms and waved American flags and were more keen on honoring their brave soldiers than protecting themselves from contagion.

The schools were re-opened on November 18, a week after Armistice Day, a decision that was controversial. On that day, 75-90% students were in attendance, but those numbers dropped precipitously.

The reopening was brief. Within a week, more than 1/3 of all students in Columbus were out due to the flu or parental fear. Kahn again closed certain Columbus schools, however the High School of Commerce, the Columbus Normal School, trade schools, and business colleges remained in operation.

According to Van Syckel, “. . . there was for a time some doubt as to whether this enforced vacation was really acceptable and entirely welcome to the students. But all doubt on this point was removed on the morning (December 2) on which the announcement came from the office of the city’s Health Board that a second closing of schools was demanded. The word carried to the seniors, assembled for an English recitation, met with such a unanimous vote of instant acceptance, and such hasty action, that it must be admitted boys still love freedom and vacation–especially the first days of it.”

On January 2, 1919, Columbus Academy once again reopened and began the second semester: “But apparently the result (if not the design) of this was to show what these men of the Academy could do in spite of obstacles. For now, as the end of the year draws near, we find in spite of this handicap, as well as many others that could be mentioned if space allowed, the work of the year has been done, exams are being faced with no more than the usual flurries and the customary anxiety,” writes Van Syckel.

Between October 1918 and June 1919, the flu killed 1,236 citizens of Columbus.

The Influenza Encyclopedia reports that, “Its excess death rate due to influenza and pneumonia during the fall of 1918 and winter of 1919 was 312 deaths per 100,000 population.

The 2020 Coronavirus may have forced our school doors to close, but it is not the first time for the Academy. Our school has survived the brunt of two world wars, and in due course, we will find ourselves back in the classroom after our second epidemic.

Thankfully, we have the luxury of 21st century technology to stay connected through Zoom calls and social media.

And to Academy students: although these times are challenging, at least it’s not 1919–we do not have final exams!

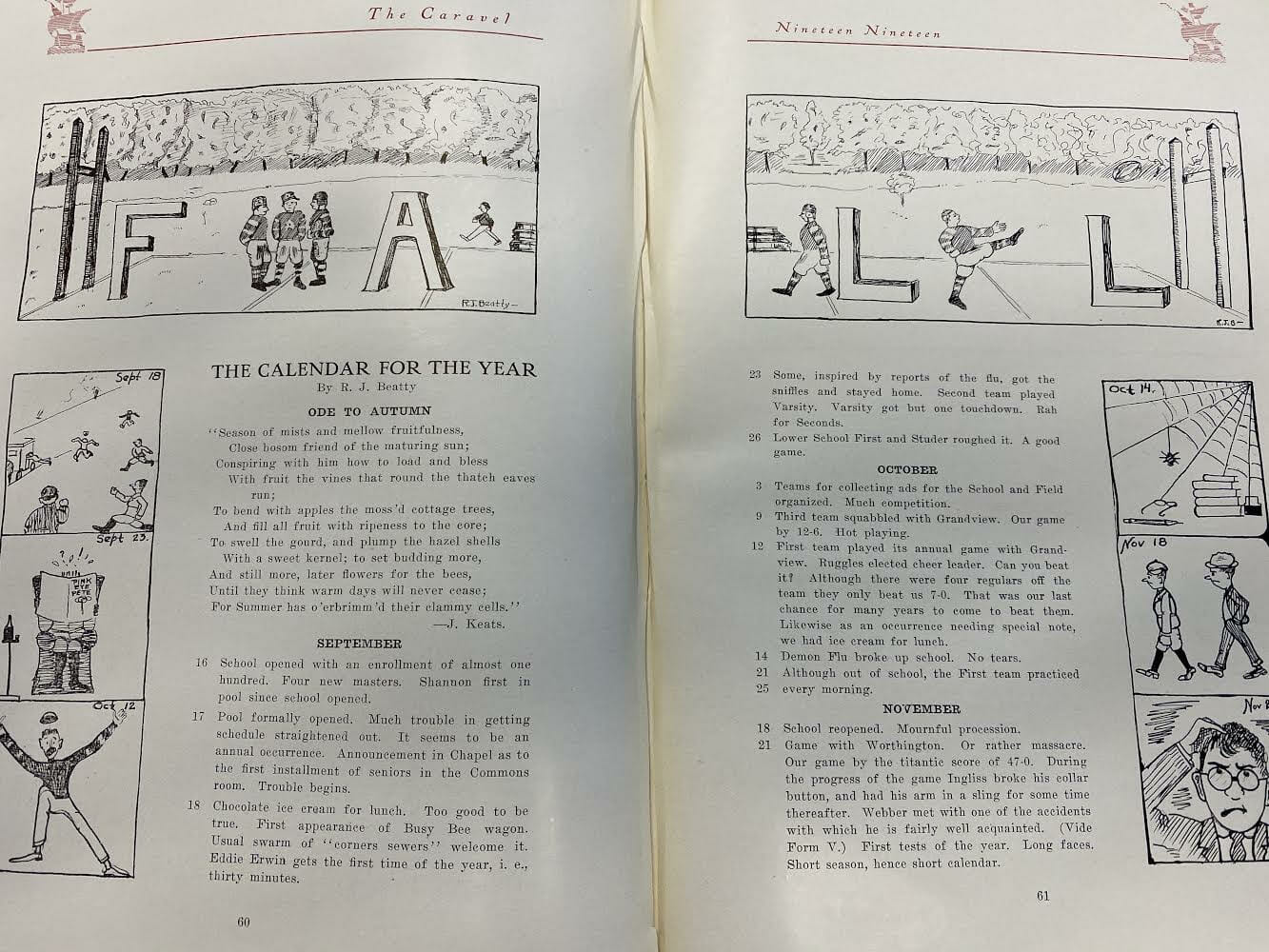

An Excerpt from “The Calendar for the Year” by R.J. Beatty

October

Teams for collecting ads for the School and Field

organized. Much competition.

Third team squabbled with Grandview. Our game

by 12-6. Hot playing.

First team played its annual game with Grand-

view. Ruggles elected cheer leader. Can you beat

it? Although there were four regulars off the

team they only beat us 7-0. That was our last

chance for many years to come to beat them.

Likewise as an occurrence needing special note,

we had ice cream for lunch.

Demon Flu broke up school. No tears.

Although out of school, the First team practiced

every morning.

*I included this poem from the month of October, the month the schools were closed. It was written by an Academy student in the yearbook. I find it parallels our experience–as our lacrosse teams were readying for their annual trips out of state; our track players were beginning their conditioning intervals; our baseball team was preparing for their first pitch off the mound; our boys’ tennis team was training for another state-tournament run; our talented actors and actresses were rehearsing for their spring musical. Like in 1918, our “Demon Flu” abruptly rippled through our routine of normalcy. While our perspectives may be over 100 years apart, some things remain the same.